The Stanford Shanghai Prison Experiment

Today, May 1st, is the one-month anniversary of the lockdown that officially started on April 1st for most of Shanghai. Many districts started way earlier. The seemingly interminable citywide lockdown has started to feel like being in prison for many. Of course, this is no social experiment à la the 1971 Stanford psychology study by Philip Zimbardo[1], but the 30-day lockdown (minimally, and counting) in Shanghai has brought new social behaviors and reactions to light. The stark, the heartrending, and the stories of desperation have been circulating on various media platforms. I thought to share instead stories of the everyday lived experience of the community – the good, the bad, the funny… and the mounting frustration.

Groundhog Day

The 1971 experiment was intended to run for 14 days, but was terminated on Day 6. In tragic contrast to that, the Shanghai lockdown was supposed to run for 4 days each in Pudong and Puxi, but has run on for much longer with no clear end date. Reminiscent of being in an actual prison, some residents in Xuhui District even found themselves with chains on their doors one morning – fire hazard or not.

Source: Weibo. A depiction of Shanghai after green fences were erected around several residences to forcibly lock people in.

On Apr 12th, the Chinese government announced a 3-tiered system to categorize residential estates according to their risk profile[2] (ie. The most recent COVID-positive case), which has been largely perceived by international media as a relaxation of rules. In truth, most estates remain in the strictest category, with residents confined to their homes (足不出户). For many, it feels like Groundhog Day – the 14-day timer to leave the estate restarts almost every day or every couple of days due to a new case. It does feel a little like Snakes and Ladders.

Source: WeChat chat groups. Depicting the game that all Shanghai residents are forced to play now.

In my estate, we weren’t even circling Day One (of 14). Because the positive case in another block refused to be transferred to centralized quarantine, our 14-day timer could not begin. So in actuality, we were perpetually in Day Zero. How depressing. This naturally sparked a lot of rage in the residents group chat, some people advocating for him to be forcibly taken away so that our timer could commence, others defending him to say that no one, given a choice, would want to go to the central facility with appalling living conditions. It was truly people against people.

A.N.X.I.E.T.Y

Stress and anxiety levels were at an all-time high at the start of the lockdown. Like a bad April Fool’s joke, my orders (that I had put in a week before) due to arrive on Apr 1st on the first day of the lockdown, were steadily cancelled one by one. This was still early days, and group buying hadn’t kicked in yet. Buying on the usual grocery apps felt like a game of Fastest Fingers First – you would literally watch your shopping cart get decimated before your eyes before you could get your payment through. I don’t think I had ever imagined that I would one day have to ration food and obsess so much over buying groceries/planning meals.

Source: My residential group chat. The government gave a bunch of *very green* bananas, prompting a resident to make this… piece of artwork. 蕉绿 (green bananas), a homophone for 焦虑 (anxiety).

As group buying came online, days became a rushed blur and endless cycle of:

Obsessively checking WeChat to keep abreast of the latest news and buys in the resident group chat

Standing by to go downstairs for the mandatory swabs – notices came with no advance notice, “Come! Down! Now!”.

Putting away groceries into the fridge, because groceries would be delivered at all hours, even at midnight. The frozen meat or milk can’t sit outside your door waiting while you finish your meetings.

Cooking two meals a day, and planning meals obsessively to use up the fresh ingredients before they spoiled

Cleaning the house

And attempting to keep up the normalcy and cadence of work

Rinse and repeat the next day… and the next 30 days.

Group buying was frantic at the start. It almost felt like standing in the middle of a virtual wet market with the auntie yelling at you to make up your mind. Hundreds of messages would come in every hour, with the almighty group leader (团长 – often residents, sometimes salespeople who sneak into resident group chats) hawking offers and threatening to shut off orders within an hour. Too bad if you were in a meeting and missed your chance to buy eggs, or milk, or vegetables. Or god forbid, the rare occasion when the opportunity to buy fresh! bread! or coffee! comes along.

Everyone’s general mood: hangry.

Source: Circulated in my WeChat circles. A skyline of veggies – the main thought that consumes most people in Shanghai these days.

Social Stratification in Stark Relief

Much like in prison, each one of us now has an ID number tagged to us. Not our identification documents, but our apartment number (eg. 8-1002: Block 8, 10th floor, 2nd unit), for that is now our alias in our resident group buying chats. No one cares for your real name, only for your unit number so that goods can be delivered correctly.

Source: WeChat chat groups.

The availability of supplies and daily way of life varies drastically from district to district, even within the same district. Stories of the elderly being left without access to food and unable to keep up with the frantic group buying are rampant. Others were unable to buy basic things like bread, either because they live in too small estates or have different purchasing habits from the rest of their community (eg. Mostly elderly in the compound, who didn’t want bread) and so could not make the minimum order quantity. Others were left with insufficient supplies and resorted to banging pots and pans in protest. On the other hand, wealthier estates, often with many expats living there, would request for premium items like cold cuts and cheese, even setting up group buys for caviar, sea urchin and premium steaks.

While the media has covered the tough lives of delivery riders and truckers, the struggles of the property management (物业) and staff have largely gone unreported and unappreciated. They have borne the brunt of the anger by residents locked up in their apartments, demanding transparency of the policies, demanding clarity of when they can finally leave their homes, demanding access to groceries. Often, the 物业 are the ones tirelessly contacting suppliers, organizing group buys and coordinating orders/deliveries. Their workplaces have become their homes; some sleep in the basement, segregated by cardboard boxes. They rise at 6am everyday to deliver goods (ranging from bags of vegetables, to cartons of eggs, to crates of water) door to door, coordinate swab tests, deliver rapid antigen kits and manage communications in the residents group chats. While they are mere instruction takers, frustrated residents take their angst out on them, having no other target. There was even news circulating of a security guard in another estate being beaten and seriously injured by an angry resident.

Amidst the struggles, kindness does prevail. A neighbor organized a charity drive to donate camping beds, pillows and blankets for the staff, while another pooled money to organize hot meals and coffee delivered to the staff every day so they wouldn’t need to cook on top of their exhausting days.

What policy? Policy, what?

While the international media has mostly picked up on positive developments – “Shanghai has lifted the lockdown… more than half the city is free to roam…” – the reality on the ground is that most people are still locked down.

Local district officials are disincentivized to use their own discretion or take risks, most choosing to err on the side of maximum conservatism. Several estates with no cases at all for 20+ days and should technically have been classified in the lowest risk tier (防范区 – can roam the neighborhood) had their estate management voluntarily upgrade them to a higher risk level (管控区 – can only stay within the residential compound). In some cases, even after 7 days of no new cases, estate management staff barred residents from leaving their apartments, keeping them at the strictest risk level (封控区) unless they obtained explicit written instructions from above.

Policy execution also varies from district to district, often inconsistent with the announced policies by the city government (and voice of authority – 上海发布). While the city had announced the shrinking of the assessment unit from residential compounds to individual blocks (ie. Each block within a compound can have their risk level assessed independently), not every district/residence adhered to this, much to the chagrin of residents. Compounds with 10-20 blocks could be completely locked down simply because there was a positive case in an individual block.

Overall, there has been a lack of transparency, coupled with multiple gaps in execution. The regular PCR tests have also been the subject of questioning, with residents reluctant to go out for tests because it increased the risk of cross-infection. Notices to go downstairs immediately for “mandatory” PCR tests often came without warning at all, sometimes at 6 in the morning. Soon, we realized that they weren’t mandatory at all – inevitably, some would miss the notices amidst the flood of messages and subsequently miss the swab altogether, to no apparent consequences. Yet, there would be threats of having one’s health code permanently downgraded to red if one missed an actual mandatory PCR. Frustration abounded. Someone in my residence suggested staging a revolt and rallied others to refuse going for the swabs. Another resident replied by simply sending a screenshot of the police warning that any non-compliance would be met with legal action and the person taken into police custody. That silenced most dissenters reluctantly.

Others questioned the scientific logic of the processes. There was an occasion we had to complete two rapid antigen tests and a PCR test all in one day. Unsurprisingly, it was met with much incredulity.

Source: WeChat chat groups. Shanghai’s icons constructed out of ART test kits.

That said, the system is starting to show signs of cracking. On Apr 26th when the government organized a compulsory city-wide swab, the system used to register residents’ swabs broke down, bringing the entire exercise to a standstill by 10am. On Apr 22nd, videos of 《四月之声 – Voices of April》[3] were circulated fervently, an endless cycle of being removed by censors and reposted by angry residents. In some places, reports surfaced of hungry residents raiding empty supermarkets, and in another, residents in Zhangjiang clashed violently with the police when the government wanted to take over their residential building to turn it into a quarantine facility[4] (to note, the Zhangjiang residential building was in a middle-class neighborhood, specifically created to attract talents from abroad).

There is a lot of anger. Many have lost faith in the government.

A New Way of Life

Overall, people are exhausted, but slowly (reluctantly) adapting to this new way of life. Panic buying has given way to “buying just in case” – you learn to stock up, because you don’t know when that product (eg. Shampoo, bread, biscuits) will be available again. Everything comes in bulk, because gone are the days when you can buy individual unit items from grocery apps. My effort to buy fruits in the early days of the lockdown ended up with me being forced to buy a whole crate of 80 apples – hey, at least apples are hardy and can last; the alternative was a crate of 10 papayas, or 22 kiwis, or 24 avocados, or 8 melons.

My apples on my living room floor, because they couldn’t fit in my fridge. Traded a few for fresh bread.

Inevitably, there is a lot of wastage and excess, because often residents end up with more than what they need, or are forced to buy bundles with other items they don’t need, simply because there is no other alternative to group buying. Not optimal when there are other people going hungry, but this is the only way now.

You experience the surprising feeling of being inordinately joyful when little “non-essential essentials” become available and get delivered – think coffee, snacks, sweets. On one occasion, someone in my block managed to slot in a bulk order for KFC. Fried chicken has never tasted this good. You learn to appreciate little luxuries. You also learn to be resourceful and creative – gotta find a way to use up that 5 heads of cabbage, and those 10 sticks of carrots you received. A mini economy has blossomed, with residents resorting to barter trading – bread for apples, vegetables for milk.[5]

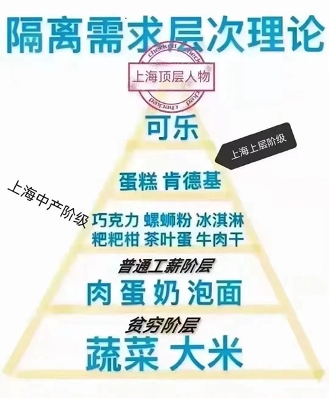

Source: WeChat chat groups. The new Shanghai Maslow’s hierarchy of value of goods today.

Everyone has had a different lived experience this April. This is not to undermine the struggles of the workers or people struggling to get sufficient food. The disillusionment and fatigue is real, and has permeated most of our consciousness.

But as we tread cautiously into May, perhaps one may be allowed to hope that there is some light at the end of the tunnel.

[1] https://www.prisonexp.org/

[2] https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-04-11/Shanghai-partially-lifts-community-lockdowns-to-reboot-city-198XETtdVS0/index.html If there has been a positive case in the past 7 days, the estate is classified as a 封控区, residents are forbidden to leave their apartments. Else, if there has been a positive case in the past 14 days, the estate is classified as a 管控区 and residents can go downstairs but not leave the residential compound. Otherwise, the estate is classified as a 防范区, and residents can leave and wander around the neighborhood but not leave the district.

[3] https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/chinas-censors-scrub-viral-shanghai-lockdown-video-online-platforms-2643081

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/6813e7d6-5ac5-4a06-bd13-4592dc8e936e

[5] https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1010249/what-shanghais-locked-down-residents-are-trying-to-buy?source=channel_home

Good write, Casatrina. Hang on there!